Should we use React in 2026?

LLMs are very good with Vanilla JavaScript

Intro

A friend of mine asked me recently, “Why should we use React in 2026? The LLMs are very good with Vanilla JavaScript (JS)!” We are facing a software development revolution with AI, and this question puzzled me, so I decided to run an experiment to answer him. Does the choice of a frontend library impact the efficiency of an AI agent when implementing identical functionality? Is there any difference between going with Vanilla JS or using a library like React when using a model to write most of the code?

I conducted this experiment to address these questions and conclude if the selection of the tech stack is still as important as before the raise of AI coding.

Methodology

To answer the above questions, I decided to compare how a model would behave when implementing the same app but with different dependencies: one using only Vanilla JS and another using React.

We decided to build a To-Do App because it has well-understood requirements: create, read, update, and delete. There is no ambiguity about what “done” looks like. Every developer knows what it should do, and so does every LLM. We then created a plan for each variant and asked the model to follow the best practices, especially the separation of concerns.

In both plans, we asked the model to use Vite as the build tool. For React, this is standard because it handles JSX transformation and hot module replacement out of the box. For Vanilla JS, we still wanted Vite because real-world frontend projects need at minimum a build step: minification, bundling, and often transpilation for older browsers. Using Vite for both kept the comparison fair: the same tooling, the same build verification (npm run build), and the same development workflow. The only variable was whether to use React.

The React plan totaled 185 lines, while the Vanilla JS plan totaled 261 lines. Vanilla JS genuinely requires more explanation. You need to describe the observer pattern for state management, manual DOM creation for each component, and explicit event delegation. React abstracts these away, so its plan is naturally shorter. This asymmetry is a feature, not a bug: it reflects the real documentation overhead that each library or framework demands.

The next step was to set up a lightweight agent harness in Python using the Anthropic SDK. We want to run each plan 10 times for each variant because LLMs are not deterministic, so we can distinguish between random variation and real patterns. Each agent had four tools: write_file, read_file, bash, and list_directory. These tools are enough to create projects, write code, and run npm commands. The harness tracked tokens directly from the response usage after each API call, accumulated totals across the agent loop, and verified builds by checking the exit code of npm run build.

All 20 agents ran in parallel using Python’s ProcessPoolExecutor, with file locking (fcntl) to safely write results to a shared CSV. No frameworks, no orchestration libraries, just ~200 lines of Python calling the Claude API in a loop. We used Claude Opus 4.5 for all runs because it’s Anthropic’s most capable model at the time of this experiment. The goal was to measure framework efficiency at peak performance, not to test whether the model could complete the task.

Results

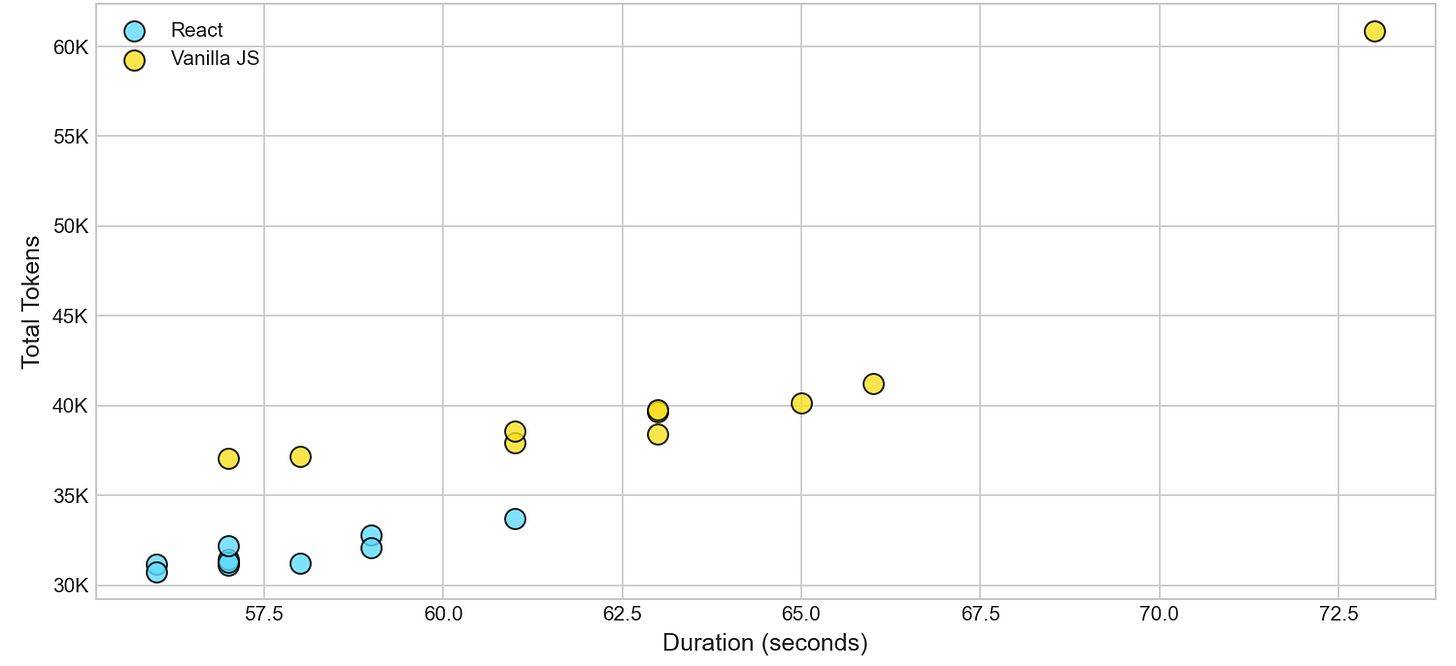

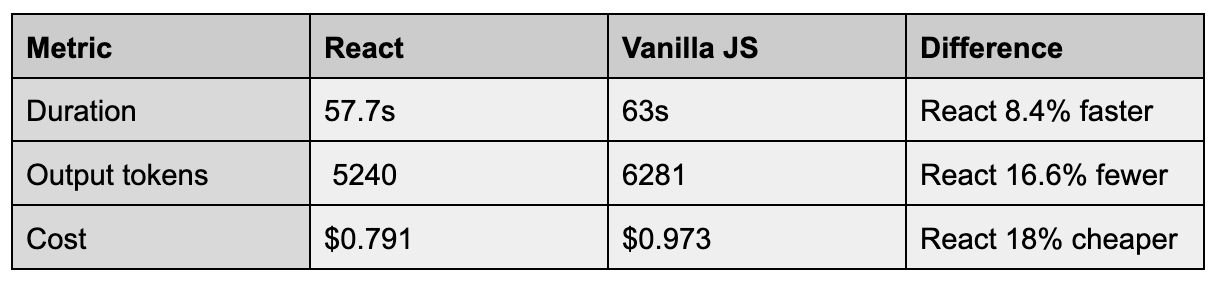

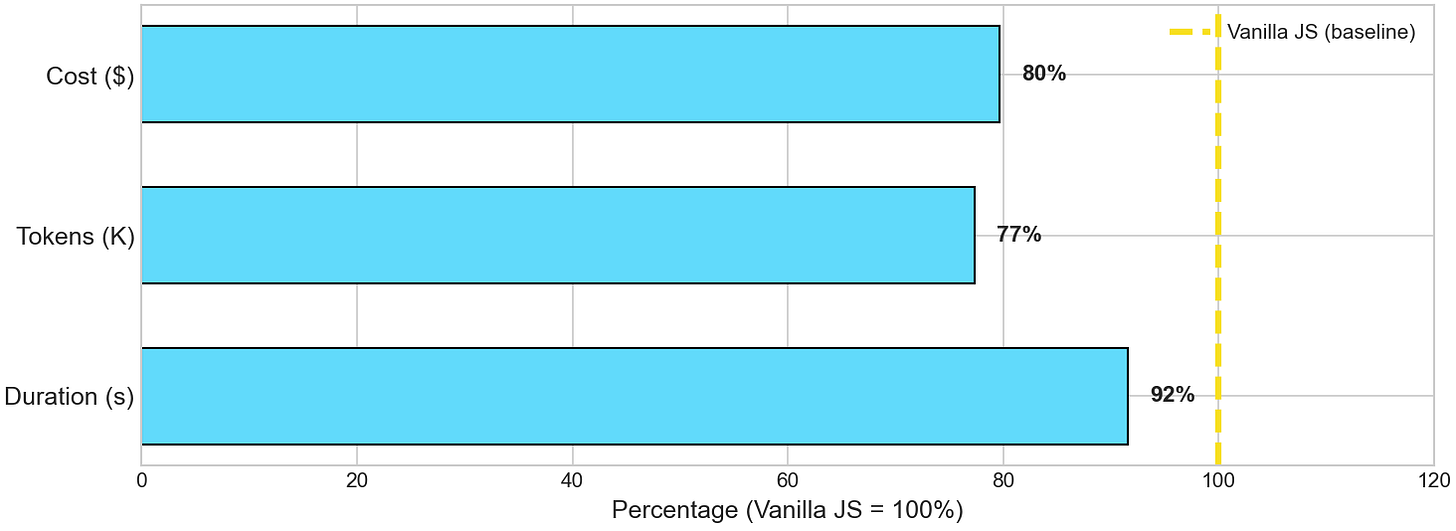

As expected, the 20 agents built the app successfully, and almost all runs required only 4 turns. Only one agent for Vanilla JS required 6 turns, which I think is not significant. My friend was right; the model is clearly good at writing Vanilla JS. The code is well-structured and easily understandable. However, the model is also very good at writing React, and there are key differences in the metrics. React was cheaper and more token-efficient in every single run. React was also faster on average.

React expresses the same application logic in fewer tokens. The model does the same amount of thinking but produces less text, which could also explain why it is quicker. In a pay-per-token world, that’s a difference that matters.

In the following table, we present the average across all metrics. Note that I used output tokens rather than total tokens because of the differences in the input tokens (the plans’ length). Output tokens measure only what the model generated: the actual code.

Beyond the averages, React was remarkably more consistent: its duration varied by only 1.6 seconds across runs, compared to 4.7 seconds for Vanilla JS—meaning React delivers not just better performance, but more predictable performance.

Wrapping up

LLMs can write Vanilla JavaScript. Opus 4.5 achieved 100% build success on both variants; the model understood DOM manipulation, event delegation, and the observer pattern just fine.

However, capability isn’t efficiency. React exists because managing DOM state manually doesn’t scale. Components drift out of sync. Event listeners leak. Re-renders become unpredictable. These problems drove developers toward declarative frameworks a decade ago, and they don’t disappear just because an AI is writing the code.

Our todo app was trivial: a few components, one data structure, and no shared state between views. Even here, Vanilla JS required ~20% more output tokens. Now imagine a larger application with hundreds of nested components, complex state dependencies, and multiple data sources, the verbosity gap compounds. Every document.createElement the model writes is a token spent. Every manual re-render is code that React would handle implicitly.

The frameworks we built to manage human cognitive load also reduce token load. React’s abstractions aren’t just convenient, they’re compression. JSX is better than imperative DOM code. Hooks are better than hand-rolled state management. When you pay per token, compression pays dividends.

This experiment tested one model, one task, and 20 runs, but the results suggest that as AI-generated applications grow in complexity, the stack you choose becomes increasingly essential. The same scaling problems that made React necessary for human developers may make it economical for AI agents.

The question was never whether LLMs can write Vanilla JS. They can. The question is whether they should, and at scale, the answer increasingly looks like no.

The whole experiment code, raw data, and generated charts are available on GitHub for consulting.